For a brief time after Reinette Long Hunt died in 1940, her distant cousins, John W. Ford and Josephine Alger of Youngstown, Ohio, owned The Grove property.

Several prominent buyers expressed interest when The Grove went up for sale, among them Mary Call Darby Collins (1911-2009), the great-granddaughter of Richard Keith Call, and her husband, State Senator Thomas LeRoy Collins (1909-1991). The other potential suitors withdrew their offers and the Collins family purchased the property in 1942.

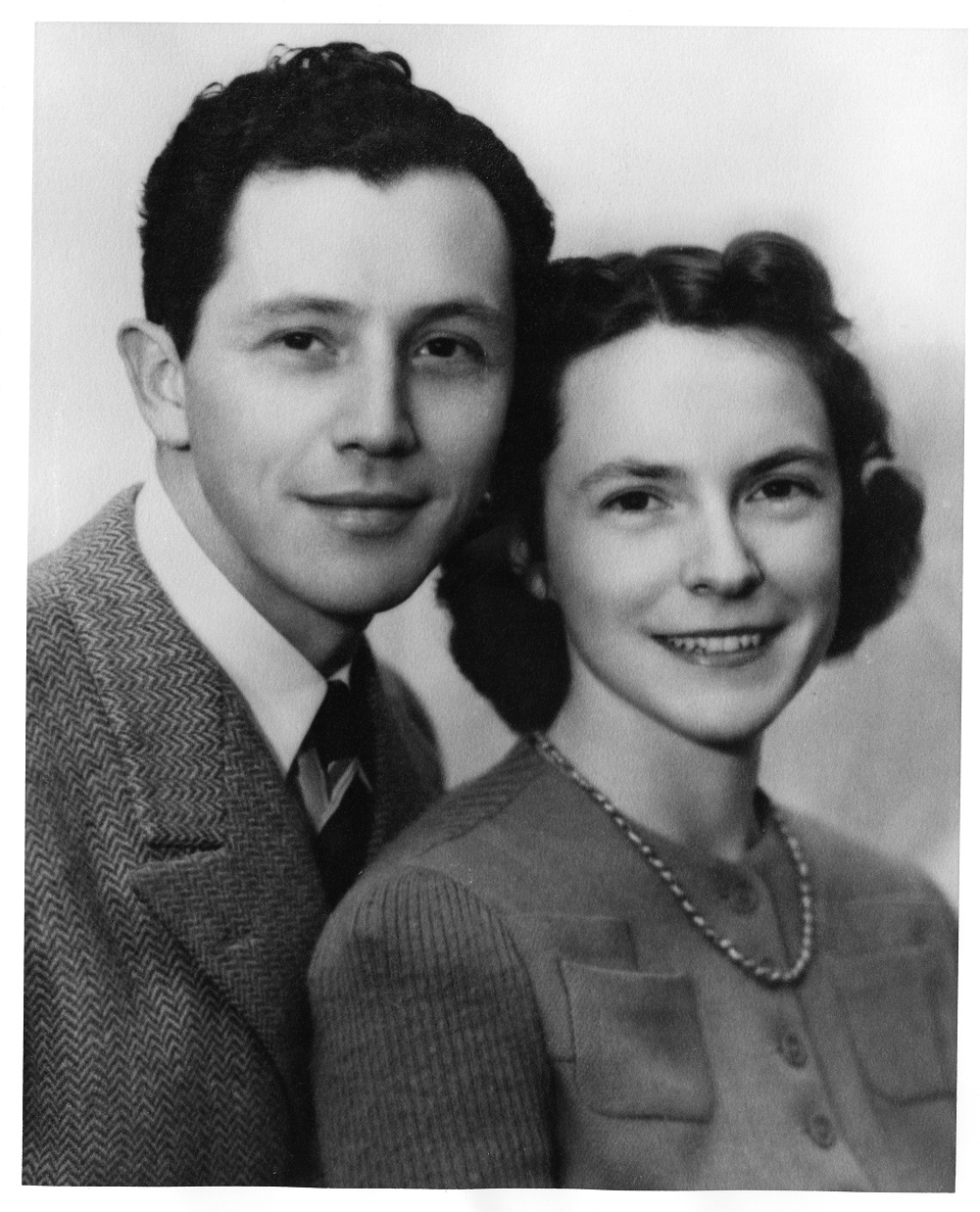

LeRoy and Mary Call Collins on their wedding day, 1932. Photo courtesy of Jane Aurell Menton.

The Collins Family, (left to right) Jane, Roy Jr., Mary Call Darby, LeRoy, Mary Call, and Darby, ca. 1955. Photo courtesy of the State Archives of Florida.

Mary Call Darby and LeRoy Collins shared deep roots in Tallahassee. Mary Call grew up in the Brevard family home on Monroe Street, just south of The Grove. She was surrounded by strong women from an early age, including her grandmother Mary Call Brevard, her aunt Caroline “Carrie” Mays Brevard (1860-1920), and her mother Jane Kirkman Brevard (1868-1932).

The Brevard Family Home, 1934. Photo courtesy of the State Archives of Florida.

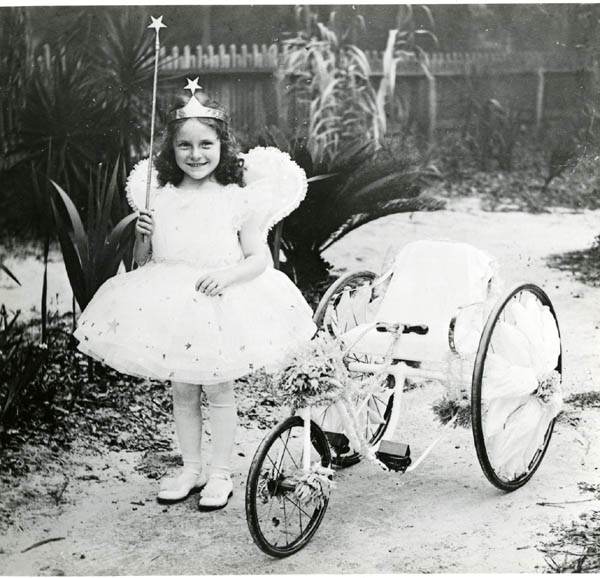

Mary Call Darby at the Brevard family house as the "Queen of the Fairies" for the May Day celebration, ca. 1917. Photo courtesy of Jane Aurell Menton.

Mary Call Darby met LeRoy Collins while she was a student at the Florida State College for Women. They married in 1932.

Thomas LeRoy Collins was born in Tallahassee, the son of a grocer. He attended local schools before leaving the state to study business, and later, to attend law school.

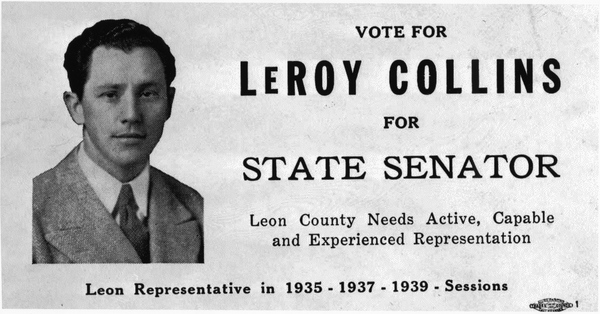

Collins returned to his hometown and established a law practice. He was elected to the state house in 1934 and the state senate in 1940. Collins resigned his seat in 1944 to serve in the Navy during World War II. He returned to the senate in 1947.

LeRoy Collins for Senate Campaign Card, ca. 1940. Photo courtesy of the State Archives of Florida

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the Collins family worked to restore The Grove. By 1950, the family had grown to include four children, LeRoy Jr., Jane, Mary Call, and Darby.

In 1952, the Collins family built an addition on the rear of the house to provide modern conveniences. This addition by the Collins family complimented the historic building and represents an early contribution to the modern historic preservation movement in Florida.

Mary Call Collins standing in a doorway dividing the original house from the new addition, 1957. Photo courtesy of the State Archives of Florida.

When elected governor in 1954, Collins and his family briefly lived in the original Florida Governor’s Mansion. In 1955, the state demolished the existing building. Governor and Mrs. Collins played a significant role in influencing the choice to design the new executive mansion as a nod to Andrew Jackson’s The Hermitage.

Mrs. Collins worked with James Cogar, Curator at Colonial Williamsburg, on a furnishing plan for the new Mansion, which was completed in 1957. Cogar and Mrs. Collins then worked together to furnish The Grove with pieces that evoked the life and times of Richard Keith Call and Ellen Call Long. For a short time in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Cogar leased The Grove from the Collins family and opened the site to the public as a museum while Governor and Mrs. Collins lived in Washington, D.C.

Postcard showing the Parlor from the first Grove Museum, 1959.

View from Adams Street of the original museum sign for The Grove, ca. 1960.

LeRoy Collins’ early political career was marked by efforts to reform Florida’s inadequate educational system, while maintaining racial segregation, and fostering a climate favorable to economic development.

While a state senator, Collins initiated legislation, known as the Minimum Foundation Program, to provide equitable funding for all pupils in Florida public schools. He supported the construction of the Florida Turnpike and helped to create the Florida Development Commission, an agency dedicated to promoting tourism.

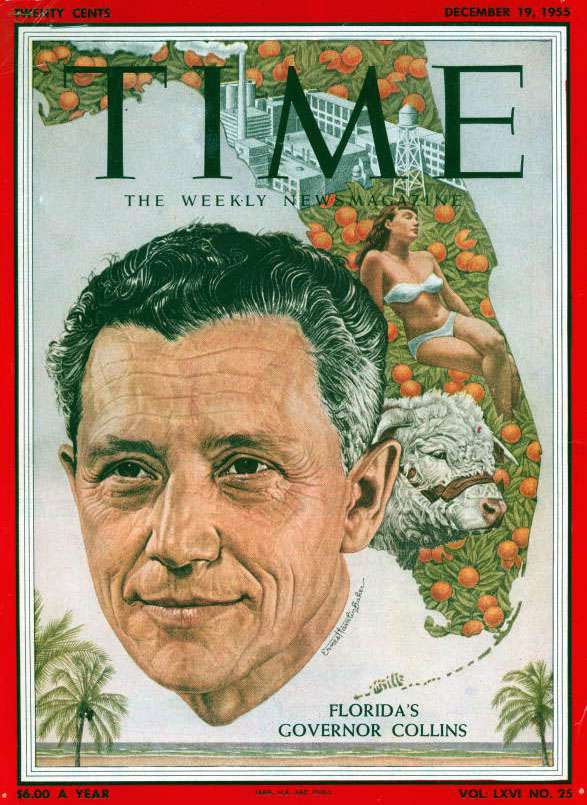

LeRoy Collins entered the race for governor when his close friend, Dan McCarty, suddenly died while in office. Collins won a special election and became Florida’s 33rd governor on January 4, 1955. As he entered office, Collins pledged to continue along the track he had established over two decades of service in the state legislature.

As governor, Collins went on to post an impressive record, including the significant expansion of the state’s community college system, an influx of industry, the completion of the Florida Turnpike, and steps towards long overdue legislative reapportionment. He also promised to approach the growing issue of race relations with the goal of maintaining segregation as Florida’s “law and custom.”

Time Magazine cover featuring Governor LeRoy Collins, 1955.

Civil rights came to define the political legacy of LeRoy Collins. During his time as Governor, Collins' views on race relations evolved from a supporter of the status quo to a proponent of expanding civil rights for African-Americans through federal legislation, bi-racial cooperation, and moderately-toned, peaceful political discourse.

In 1955 and 1957, Collins denounced the Florida state legislature’s attempts to nullify the US Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown vs. Topeka, Kansas Board of Education (1954). He warned the legislature about their use of extremist rhetoric in response to African-Americans' calls for civil rights. He considered the legislature's position that the Brown decision was "null and void" in Florida to be "anarchy and rebellion against the nation." He further stated that it "constituted an evil thing, whipped up by the demagogues and carried on the hot and erratic winds of passion, prejudice and hysteria." (Read Collins' entire response to the Interposition Resolution here, courtesy of the State Archives of Florida.)

Collins came to see segregation as "morally wrong," "unchristian," "undemocratic," and "unrealistic," which he stated clearly in statewide televised address in March 1960, when he also advocated for dialogue and reconciliation following sit-in demonstrations in Tallahassee.

When commenting on the work of civil rights demonstrators, Collins proclaimed: "We can never stop Americans from struggling to be free. We can never stop Americans from from hoping and praying that some day in some way this ideal that is imbedded in our Declaration of Independence is one of these truths that are inevitable that all men are created equal, that, that somehow will be a reality and not just an illusory distant goal." (Read the entire speech here, courtesy of the University of Florida Digital Collections.)

Collins’ progressive, moderate tone on race relations attracted considerable attention, leading to his selection as the Permanent Chairman of the 1960 Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles.

Governor Collins at the Democratic National Convention, 1960.

Governor Collins standing with John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson at the Democratic National Convention, 1960.

Following the 1960 DNC, Collins became President of the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) in Washington, D.C., a position he held for three years. During his time as President of the NAB, Collins challenged broadcasters to create programming that benefited the public. He openly criticized the techniques used by tobacco companies to market cigarettes to children and also called for less violence on television.

While in Washington, Mrs. Collins became involved with the Mount Vernon Ladies Association, one of the leading historic preservation organization in the country. She applied her talents and lessons learned at The Grove and the Florida Governor’s Mansion to the ongoing efforts to preserve and share the legacy of George Washington.

Mary Call Collins standing in front of Mount Vernon while serving as Vice Regent for Florida to the Mount Vernon Ladies Association, 1963. Photo courtesy of Jane Aurell Menton.

In 1963, President Kennedy appointed LeRoy Collins to be Undersecretary of the US Department of Commerce. Collins remained with the Department when Lyndon B. Johnson became president following Kennedy’s assassination. Johnson soon after appointed Collins to head a new federal agency created by the Civil Rights Act of 1964, known as the Community Relations Service (CRS).

As Director of the CRS, Collins was responsible for working with communities experiencing conflict over race relations following the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

LeRoy Collins with President Johnson at the signing of the Civil Rights Act, 1964.

Collins' most prominent role as head of the CRS came in Selma, Alabama, in March 1965.

President Johnson sent Collins to Selma following “Bloody Sunday,” in which Alabama state police violently attacked civil rights marchers attempting to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Collins devised a solution and presented his plan to the opposing sides. Working through the night before the next planned march, Collins convinced state officials to restrain the police and allow activists to proceed.

Ultimately, Collins, working on behalf of President Johnson, helped to avoid a repeat of the ugly violence broadcast across the country just days before.

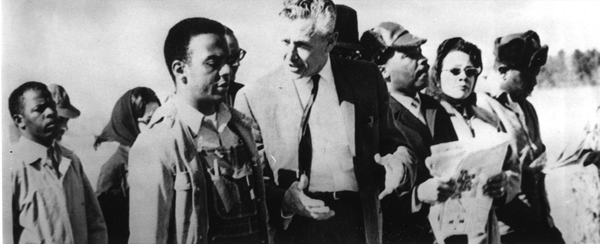

Left to right: John Lewis, Andrew Young, LeRoy Collins, Martin Luther King Jr., and Coretta Scott King, near Selma, Alabama, 1965.

By intervening on behalf of the federal government at Selma, Collins dealt a fatal blow to his future political aspirations.

When he ran for the US Senate in 1968, opponents widely publicized a photograph taken of Collins at Selma. The photograph showed Collins walking alongside prominent civil rights leaders. Collins' opponents portrayed him as too liberal on civil rights, and as a result he lost the election.

Following his defeat, LeRoy and Mary Call Collins returned to Tallahassee. He rejoined his law practice and she resumed her commitment to historic preservation.

In 1971, Collins published Forerunners Courageous, a collection of short stories on Florida history. He continued his involvement with Florida politics, particularly constitutional revision, and served on the 1977 Florida Constitution Revision Commission.

Mary Call Collins dedicated considerable time to local historic preservation projects. She lent energy and her name to the efforts to save the historic Union Bank building and the Old Capitol from destruction. The restored bank now serves as a satellite facility of the Southeast Regional Black Archives, managed by Florida A&M University. The Old Capitol is now home to the Florida Historic Capitol Museum.

LeRoy and Mary Call Collins in front of The Grove, 1980. Photo courtesy Jane Aurell Menton.

The Collins family sold The Grove to the State of Florida in 1985, entrusting the property to the Florida Department of State and ensuring its future use as a museum. Governor Collins passed away at The Grove in 1991. He was followed in death by Mary Call Collins in 2009. Both are laid to rest in the family cemetery on the property.

Visitor Parking:

902 N. Monroe Street, Tallahassee, FL 32303

House and Grounds

Wednesday - Saturday: House tours on the hour starting at 10 a.m. Last tour is at 3 p.m.

Closed Sunday, Monday, and Tuesday

Group Tours: Tours for groups of ten (10) or more are available at $1.00 per guest. For group tours, please contact the museum in advance to make arrangements.